Tag: Science

Ep. 2 Transcript: “Strong Nuclear Force”

Here is the transcript for tonight’s episode:

Hello, and welcome to episode two of “Owen Drake’s Big Ideas.”

Last week, I explained that gravity is not in fact an attractive force between bodies, as is generally believed, but rather the effect of an omnidirectional energy flow that is present in (and generated by) empty space. In essence, empty space behaves in many ways like a moving fluid, flowing in every direction at once, passing through “solid” objects (which are themselves mostly empty space), and being slightly impeded by them, like rocks in a stream. I have dubbed this ever-present omnidirectional energy flow, the “Omniflow”.

The Earth impedes the Omniflow, so the flow we feel coming up through the Earth is reduced in comparison to the unimpeded flow we feel from above, so we are pressed to the Earth, by the flow, like the experience we know as “gravity”.

Today I will be explaining the relationship between the Omniflow and the strong nuclear force, which binds together atoms.

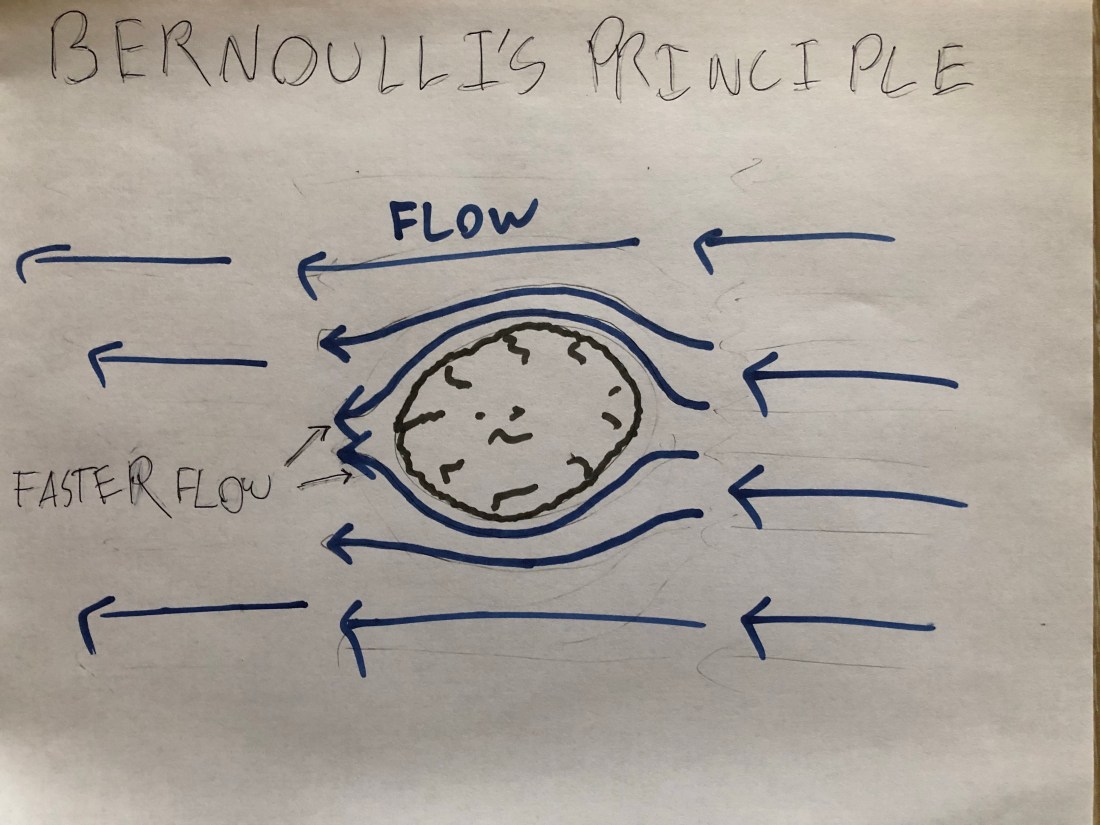

We are beginning to see how empty space behaves like a moving fluid, and when dealing with moving fluids, there is nothing more basic than the Bernoulli effect. Bernoulli’s principle actually deals with a fluid’s pressure, but we are only concerned with flow velocity (because the Omniflow is not composed of interacting particles, it does not exert static fluid pressure, only flow pressure).

The important part for us is how parts of a moving fluid must accelerate in order to pass around an object in the fluid’s flow path. The fluid that must change direction in order to go around the object ends up with a longer path to follow than the fluid going straight, so, in order to stay with the stream, the disturbed fluid must accelerate, so that it can cover the longer path in the same amount of time as the rest of the fluid that was not disturbed by the object. (See illustration #1) This is an important concept to understand, and is the basis of much of fluidity theory, as the Omniflow experiences this same effect, when it has to pass around subatomic particles (rather than pass between them, as it does the majority of the time).

I should preface this by saying that this segment is highly theoretical, even in comparison to the astronomically theoretical nature of the Omniflow theory itself. This portion of my work has not been based on or yet compared to the advanced mathematical descriptions of quantum behavior, and relies entirely on summaries of that behavior, and physical approximation. But some of the concepts will be essential elsewhere, so I think it’s still worth taking a look at these early stages.

For those not familiar, the strong nuclear force is responsible for binding together the smallest particles that exist. It binds together groups of quarks, to form protons and neutrons, and it binds groups of protons and neutrons together, to form atomic nuclei.

Because protons are positively charged, they ought to repel each other by the electromagnetic force, which they do, at certain distances. But when they get very close together, they are pulled together by an attractive force much stronger than their electromagnetic repellant force. This is known as the strong nuclear force, and I believe it can be framed in terms of fluidity theory.

Quarks are the smallest things we know of. They bunch together to form protons and neutrons (and some other things besides). In the analogy of a stream of water, picture a quark as a single carbon atom. This single atom does not impede the stream, because it will act as a part of the stream. But if you clump several such atoms together, there will be interference in the flow, on the molecular level.

Quarks work like this in the Omniflow. They are too small to have an individual effect on the flow, but several bound together will cause a disturbance. And, they are bound together by the Omniflow itself. Once two or more quarks come into contact, they experience no flow pressure from the area of contact with the other quark, because there is no flow contact there. The result is maximum flow pressure pushing the quarks together. (See illustration #2)

Once there is a clump of quarks, in the form of a proton or a neutron, the Omniflow experiences disturbance, like a rock in the stream. Recalling Bernoulli’s principle, it would follow that there are areas of high velocity Omniflow surrounding all subatomic particles. When particles are at a distance from each other, the high velocity streams have had time to remerge with the dominant flow, and the effects are only felt as gravity.

But when particles get very close to each other, these high velocity streams interact directly with the other particle. At near distance we can expect that the high velocity streams have a repellant force on the other particle, which might help explain why it is so hard to get particles very close together. (See illustration #3)

But we are now concerned with the next point, at which the high velocity streams merge. I call this the high velocity bypass state. The particles are so close that the high velocity streams move fluidly from the area of one particle to the next. At this point the particles stop feeling the full energy of the other particle’s high velocity flow, and you are left with an area of relatively low flow between the particles, so they are forced together by the Omniflow, just like quarks. (See illustration #4)

But unlike quarks, protons and neutrons never come completely into contact. This is because the Omniflow in direct contact with the particle must always complete the full circuit around the particle. It cannot break away into a bypass state like the neighboring high velocity flow, because there is no way for empty space to separate from matter.

So the border flow must make the full trip around, and it is the longest possible trip, which gives that section of the flow the highest possible velocity, so I dub it super high velocity flow. When the super high velocity flow region of one particle overlaps that of the other, they form a slipstream between the two particles, which I call the super high velocity exchange state. These combined super high velocity flows generate sufficient flow pressure to resist the Omniflow pressure from outside the system, so the particles are held apart at a distance of about 0.7 fentometres. (See illustration # 5)

And this, quite simply, is how the Omniflow is responsible for what is known as the strong nuclear force.

If you’re thinking now, “but Owen, if the Omniflow accelerates around matter, wouldn’t the flow coming through the Earth actually be faster than the flow coming from space, and so shouldn’t we be propelled away from the Earth instead of pushed toward it?”, well, you can check out my next installment on Fluidity and Relativity, for answers to that question, and more.

For further fun in the world of physics, I suggest the hilarious book by renowned nuclear physicist Richard Feynman, titled “Surely You’re Joking, Mr. Feynman?”

I’m Owen Drake. Thanks for listening. Good night.

Ep. 1 “Gravity”

Ep. 1 “Gravity”

Here is the transcript for tonight’s episode (which I will be publishing at 5 PM Pacific Time):

Good evening, and welcome to the inaugural episode of my new podcast: “Owen Drake’s Big Ideas.”

Thank you so much for joining me for this special first installment. In honor of the passing of the great Stephen Hawking, I will be dedicating this episode to gravity, and the nature of the Universe.

As many of you may know, at present scientists are able to accurately describe and predict what gravity does, but remain at a loss as to the why and how. There is still no consensus, nor even a dominant theory, as to what the force of gravity actually is. We can say it is caused by objects with mass, but why objects with mass exert a pull on other objects, nobody knows.

The theory of relativity posits the phenomenon as a curvature in “spacetime”, which causes smaller objects to sort of “roll” toward the larger ones. Think of a baseball, on a mattress. Now put a bowling ball down beside it. The bowling ball causes a curvature of the mattress, and the baseball rolls toward it. Now extend this concept to three dimensions, and you can imagine that the Earth is similarly bending the fabric of space, in all directions, and we are pulled onto it, like the baseball onto the bowling ball.

The problem with this analogy is that it relies on a previously existing, underlying force of gravity. In the bowling ball example, it is not really the curvature of the mattress which propels the baseball, it is the gravity pulling it down— the curvature merely directs its path. Even if you forced the bowling ball into the mattress by hand, without gravity the baseball never rolls. So it’s not really the curvature of the mattress that creates the pull, but the underlying gravity, which remains unexplained. Likewise, the Earth may curve the fabric of space, but that curve only contributes to planetary motion if there is already something exerting a force.

So what is this mysterious pull? And why is it so elusive?

I believe that a unifying theory of gravitational pull cannot be invented, because the force of gravity is not a pull at all, but a push.

This notion, is derived from what I have termed the “non-stuff” theory of the universe, which goes like this:

“Stuff” is everything we “see”, so to speak, everything that exists, all matter, and physical reality, including light, and even anti-matter. Non-stuff makes up the rest of space. It is the nothing, in opposition to our something, and the ontological opposite of stuff in every way.

The natural state of stuff is to exist. That’s what makes it stuff. It exists. It is. But what about the space where there is no stuff? Thanks to particle physics, we know that even solid matter is mostly empty space, which makes sense. Without empty space, reality would just be a soup of formless matter, like we believe it was in the very first moments following the Big Bang.

It was the areas of nothing that gave shape to something.

So, we can say with confidence that in order for something to exist, nothing must also exist. And this was the source of the first ever existential crisis. Because while the natural state of something is to exist, the natural state of nothing is not to exist. And so by the presence of differentiated somethingness (aka “stuff”), nothingness, whose natural state is non-existence, is compelled into a partial state of existence, in the space around the stuff. I call these areas of nothingness “non-stuff.”

Furthermore, stuff’s natural state is particular. Galaxies are made up of star systems which are made up of planets like Earth which are made up of organisms which are made of cells which are made of molecules which are made of atoms which are made of sub-atomic particles which are made of quarks, and there is no reason to assume it stops there. Non-stuff being in every way the opposite of stuff (as it must be in order to be truly nothing, which it must be to hold space for the existence of something), the natural state of non-stuff must be whole. If stuff is inherently divisible, and divided, non-stuff must be inherently indivisible, and undivided.

Thus the presence of stuff creates a physical as well as an existential crisis for non-stuff. Without the presence of stuff, non-stuff may rest in its natural state, of being undivided, undifferentiated, and nowhere. But anywhere you find stuff, non-stuff becomes divided—disturbed from its natural state of wholeness. The resulting pressure non-stuff exerts on stuff, in its effort to return to its natural state of being completely whole and empty, is what we observe and know as the force of gravity.

It appears to us that we are pulled toward the Earth, by the Earth, but in fact we are being pushed in every direction by the pressure of all the non-stuff in the universe. Because the Earth has a lot of stuff in it, and the mostly empty space immediately above our heads does not, there is more pressure from above than from below, because there is more non-stuff directly above us than below us.

Imagine a flowing stream of water. A rock in the water impedes the stream, but only directly around the rock. Then the stream reunites and flows smoothly. The pressure exerted by non-stuff works in this way as well: like a current.

Non-stuff cannot exert a force on stuff in what we consider the traditional manner, by imparting energy through the interaction of particles, because there are no material particles of non-stuff. But its need to return to its natural state of emptiness is experienced by matter as an omnidirectional current, which is locally impeded by the presence of matter, creating the illusion of a gravitational pull.

And what a powerful illusion it is. So powerful that for centuries humanity’s greatest minds have been able to develop formulas and models to predict the behavior of the material universe to a point of near-perfect accuracy. So what benefit is the non-stuff theory?

One of the big unanswered questions in astrophysics is why the universe is expanding, when it appears that, based on the amount of matter in the universe and its combined gravitational effects, the universe should instead be shrinking. The non-stuff model may help explain this.

Imagine that instead of the universe, God made two marbles, and placed them a few widths apart from each other, and that’s it. That’s all that exists in the universe.

Using the gravitational model, these two marbles would exert a pull on each other, causing them to move toward each other, eventually coming into contact. But using the non-stuff theory, the opposite occurs. This hypothetical universe has very little non-stuff, just enough to fill in the space between the particles of the marbles, and the space between the marbles themselves. Beyond the marbles, in the other directions, there is no non-stuff, because there is no stuff, and the nothingness is in its natural state of emptiness, and whole nonexistence. You cannot measure the space beyond the marbles, without adding stuff to the equation.

But between the marbles is an area where, in order for the marbles to exist, space must exist, aka, non-stuff. So all the non-stuff exists in the space between the two marbles, but not beyond, so the marbles only feel pressure from that direction (the direction of the other marble). So, pressured from within, they move outwards, away from each other. What’s more, as the distance between the marbles increases, so does the quantity of non-stuff between them, and so the pressure increases, causing the marbles to actually accelerate.

And this is similar to the observed behavior of our expanding universe.

You could sum up the whole thing like this: it is not that matter attracts matter, but that empty space repels matter.

For further reading on the topic of nothing, I recommend the Tao Te Ching.

Thanks for listening. I’m Owen Drake. Good night.